A hero is an ordinary person who finds the strength to persevere and endure in spite of overwhelming obstacles – Christopher Reeve.

I want to tell others about all the remarkable people I’ve known who’ve struggled with depression. While they’re not paladins that ride into medieval battle swinging swords atop snorting mares, they fight a different kind of battle. And one no less heroic.

Many of the best people I’ve been privileged to know struggle with depression every day. While they don’t have shiny medals pinned on their lapels, there is an unmistakable strength in them – even if they don’t see it. I know it’s real because I see and feel it – just like when I am in a grove of giant and majestic pines during a walk in the forest that must withstand the fury of a winter’s storm in January.

A Hero Steps Forward

Take Bob Antonioni. Bob’s story appeared in Esperanza magazine’s regular column, “Everyday Heroes”. He had a budding political career in the Massachusetts State Senate and a law practice. Despite holding such a public position, Bob took the courageous step to disclose that he suffered from clinical depression in the hope of letting others know it was okay – there wasn’t anything to be ashamed of:

“Telling his story has become another tool to chip away at stigma. Yet he remembers his trepidation when he disclosed the truth in a November 2003 interview with a local newspaper.

‘I had misgivings,’ he admits, ‘but I guess I didn’t give people enough credit. All I heard were thank yous —the complete opposite of what I expected.’ In fact, Antonioni was re-elected twice after that. He retired from public office in 2009 to have more time for himself and his family, but continues to practice law and pursue his advocacy work.”

To me, it says something wonderful about the human spirit that against such a formidable foe as depression, people keep fighting to get better. And many triumph. Just like Bob.

The Black Dog

A few weeks ago in Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper, there was a great piece, Ill to Power. The article was about Winston Churchill’s life-long battle with depression written by the author of the new book, A First-rate Madness. Here, he describes Churchill’s struggles:

A few weeks ago in Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper, there was a great piece, Ill to Power. The article was about Winston Churchill’s life-long battle with depression written by the author of the new book, A First-rate Madness. Here, he describes Churchill’s struggles:

“There is no doubt that he had severe periods of depression; he was open about it – calling it, following Samuel Johnson, his ‘Black Dog.’ Apparently his most severe bout of depression came in 1910, when he was, at about age 35, Home Secretary. Later in his life, he told his doctor, ‘For two or three years the light faded from the picture. I sat in the House of Commons, but black depression settled on me.’ He had thoughts of killing himself. ‘I don’t like standing near the edge of the platform when an express train is passing through’.”

Like Churchill, Abraham Lincoln struggled with major bouts of depression. In the book Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Fueled a President to Greatness, Lincoln writes about a cloud over him that every bit matches Churchill’s darkness:

“I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were felt by the whole human race, there would not be one cheerful face left on earth”.

Lincoln, who many say was one of this country’s greatest heroes, apparently did not feel like one all the time.

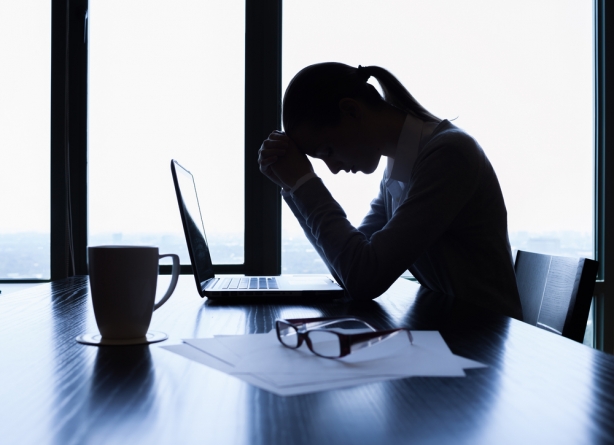

Hard to Feel Like a Hero

Most people depression — in some fundamental sense –feel broken. This conclusion is fueled by the depression itself – both biological (sleep, appetite, energy levels) and psychological (e.g. “Nobody really cares about me”, “I stink at my job” or “My depression will never end”). But this brokenness isn’t just an “inside job” – crummy stuff they tell themselves about themselves. Other people or events in a depressive’s daily orbit serve-up damaging assessments and innuendos about a depressed person’s behavior or personhood.

Others may tell them that they are letting them down at the office or not contributing enough to family responsibilities – yes, loved ones can get fed up with the depressed person’s withdrawal from the family, the inability to do chores he/she used to do and the depressed person’s sourpuss. Or, they deny the immensity of the suffering of the depressive by minimizing it: “Don’t worry, things will get better. You’re just in a slump.”

We sense that their agenda isn’t so much about helping us get better, as it is about them their needs. Why else would we feel so much crappier and lonely after such exchanges? It isn’t as if their needs aren’t important, but shouldn’t our mental health be at least as important?

Then there is the cultural stigma – a cloud of ignorance, fear and misunderstanding – surrounding depression. American culture tends to see depression as a moral or personal weakness; the “just-get-over-it” rants of a society that likes simplistic answers to complicated problems. Dr. Richard O’Connor, in his book Undoing Depression, captures some the irony of how our society sees depression as different from – or maybe not as real as — other forms of illness:

“Where’s the big national foundation leading the battle against depression? Where is the Jerry Lewis Telethon and the Annual Run for Depression? Little black ribbons for everyone to wear? The obvious answer is the stigma associated with the disease. Too much of the public still views depression as a weakness or character flaw, and thinks we should pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.

And all the hype about new antidepressant medications has only made things worse by suggesting that recovery is simply a matter of taking a pill. Too many people with depression take the same attitude; we are ashamed of and embarrassed by having depression. This is the cruelest part of the disease: we blame ourselves for being weak or lacking character instead of accepting that we have an illness, instead of realizing that our self-blame is a symptom of the disease. And feeling that way, we don’t step forward and challenge unthinking people who reinforce those negative stereotypes. So we stay hidden away, feeling miserable and yourselves for ourselves for our own misery”.

Renaming One’s Walk through Depression as Heroic

Why can’t we re-imagine our self-image in relationship to our depression in a more positive light? Why can’t we think of our battles with depression as, in fact, heroic? Instead of counting all of times that depression has gotten the better of us and knocked us to our knees, how about giving ourselves credit for all of the times that we have triumphed over depression (perhaps even in the simplest ways); the times that we have risen to the occasion in spite of our melancholy and the moments that we have looked depression in the eye and said, “no more.” Make no mistake about it that takes gumption – lots of it! And I’ve witnessed scores of people say “that’s enough.” While talking back to depression isn’t a panacea, it may be a healtier way for us to cope rather than succumb to it.

Viewing yourself as a hero is a constructive and healing experience for people with depression. It doesn’t deny that we struggle with it sometimes, but it more importantly doesn’t deny the power we actually do have over it and the courage it takes to deal with it to the best of our ability each day.

In his article “The Continuing Stigma of Depression” psychologist Jonathan Rottenberg writes about the stigma for those who have recovered from depression:

“My hunch is that the disease/defect model of depression, is unwittingly contributing to the ongoing stigma of depression. Through the lens of the disease model, the legions of the formerly depressed are a “broken” people who need lifelong assistance. I would like to see a more revolutionary public education approach, with campaigns that emphasize the unique strengths that are required to endure depression. Even if a person is helped by drugs or therapy, grappling with a severe depression requires enormous courage. In many ways, a person who has emerged from the grip of depression has just passed the most severe of trials in the human experience. If we acknowledge that surviving depression requires a special toughness, we will not see formerly depressed people as a broken legion, but as a resource who can teach us all something about overcoming adversity”.

Things to Consider

– Maybe we fall down 30 times a day, or maybe it’s just a stumble, but we have to regain our balance and get up. As the old Zen saying goes, “fall down seven times — get up eight.” That, my friends, is heroic. Just remember that when you fall and get up – YOU are that hero.

– We must remember that when we are in a depression, it isn’t easy to feel like a hero — just think of Honest Abe. But the depression will pass. So don’t be too hard on yourself if you don’t feel heroic all the time.

– We should not condemn ourselves when we are down, but pick ourselves up and remember that we are, truly, remarkable people.

As writer Andrew Berstein once wrote: “A hero has faced it all: he/she need not be undefeated, but he/she must be undaunted.”

There’s some interesting research to suggest that happy people view the world through certain comforting illusions, while depressed people see things more realistically. [i] For instance, the illusion of control. You can take a random sample of people and sit them in front of a video monitor with a joy stick, and tell them their joy stick is controlling the action of the game on the screen. (But the point of experiment is that it actually doesn’t). Depressed people will soon turn to the lab assistant and complain that their joy stick isn’t hooked up correctly. Normal people, on the other hand, will go on happily playing the game for quite some time.

There’s some interesting research to suggest that happy people view the world through certain comforting illusions, while depressed people see things more realistically. [i] For instance, the illusion of control. You can take a random sample of people and sit them in front of a video monitor with a joy stick, and tell them their joy stick is controlling the action of the game on the screen. (But the point of experiment is that it actually doesn’t). Depressed people will soon turn to the lab assistant and complain that their joy stick isn’t hooked up correctly. Normal people, on the other hand, will go on happily playing the game for quite some time.

Procrastinators have some big false assumptions about how work works. They assume that really productive people are always in a positive, energetic frame of mind that lets them jump right into piles of paper and quickly do what needs to be done, only emerging when the task is accomplished. On the contrary, motivation follows action instead of the other way around. When we make ourselves face the task ahead of us, it usually isn’t as bad as we think, and we begin to feel good about the progress we start making. Work comes first, and then comes the positive frame of mind. Closely allied to this misunderstanding about motivation is the idea that things should be easy. Depressed people assume that people who are good at work skills always feel confident and easily attain their goals; because they themselves don’t feel this way, they assume that they will never be successful. But again, most people who are really successful assume that there are going to be hard times, frustrations, and setbacks along the way. Knowing this in advance, they don’t get thrown for a loop and descend into self-blame whenever there’s a problem. If we wait until we feel completely prepared and feeling really motivated, we’ll spend a lot of our lives waiting. See my page on developing greater

Procrastinators have some big false assumptions about how work works. They assume that really productive people are always in a positive, energetic frame of mind that lets them jump right into piles of paper and quickly do what needs to be done, only emerging when the task is accomplished. On the contrary, motivation follows action instead of the other way around. When we make ourselves face the task ahead of us, it usually isn’t as bad as we think, and we begin to feel good about the progress we start making. Work comes first, and then comes the positive frame of mind. Closely allied to this misunderstanding about motivation is the idea that things should be easy. Depressed people assume that people who are good at work skills always feel confident and easily attain their goals; because they themselves don’t feel this way, they assume that they will never be successful. But again, most people who are really successful assume that there are going to be hard times, frustrations, and setbacks along the way. Knowing this in advance, they don’t get thrown for a loop and descend into self-blame whenever there’s a problem. If we wait until we feel completely prepared and feeling really motivated, we’ll spend a lot of our lives waiting. See my page on developing greater