Sigmund Freud used to refer to depression as anger turned inward. While many people may regard this as an overly simplistic approach to the most common mental health disorder in the world, there is no doubt that anger plays a significant role in depression. As one study from 2016 found, when it comes to emotional disorders in general, the presence of anger has “negative consequences, including greater symptom severity and worse treatment response.” Researchers concluded that “based on this evidence, anger appears to be an important and understudied emotion in the development, maintenance, and treatment of emotional disorders.” When it comes specifically to depression, science seems to be further supporting Freud’s theory, showing more and more how anger contributes to symptoms. A UK study from 2013 suggested that going inward and turning our anger on ourselves contributes to the severity of depression.

Having worked with depressed clients for more than 30 years, these findings were not surprising to me. Many of the people I’ve worked with who struggle with depression also share the common struggle of turning their anger on themselves. As much as I try to help my clients express their anger rather than take it on and turn it inward, I witness first-hand how hard it often is for people to interrupt this process. It’s a challenge for them to recognize the nasty way they treat themselves; they are significantly more critical of themselves that they are of others.

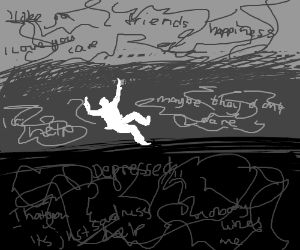

People who suffer from depression often have intense “critical inner voices” that perpetuate feelings of unworthiness and shame. When they listen to this inner critic, they not only feel more depressed, but they also find it much more difficult to stand up to their depression. This includes acting against their critical inner voices, taking positive actions that could help them feel better about themselves (like engaging in activities they enjoy), and being more social.

Getting angry at these “voices” can be liberating, but that means getting in touch with our core feelings of anger rather than aiming it at ourselves. Dr. Les Greenberg, the founder of Emotionally Focused Therapy, describes an important difference between adaptive anger and nonadaptive anger. Anger is an adaptive response when it motivates you to assertive action to end a violation. For example, when we may feel angry at the cruel way we treat ourselves today, we’re in touch with our adaptive anger, and we feel like we’re on our own side. Letting ourselves feel and express adaptive anger can help us feel less burdened, freer, and more in touch with our real self.

Maladaptive anger, on the other hand, affects us negatively. For one thing, it can contribute to feeling victimized, sulky, or stuck in a feeling of being wronged. Examples of maladaptive anger turned inward can include feeling overly critical toward ourselves, hating ourselves, or seeing ourselves as powerless, pathetic, or helpless. The generally dysfunctional responses that result from maladaptive anger are based on emotional schema from traumatic experiences in our past. Often, our critical inner voice is at the root of maladaptive anger, driving us to remain in a state of frustration and suffering.

We can almost feel the difference between maladaptive anger dragging us down and deeper into a state of anxiety or depression and adaptive anger relieving us of a heavy burden, lightening us emotionally, and contributing to our taking constructive actions. While it can feel scary to face these deeper, core emotions, we must access adaptive emotions to transform our maladaptive emotions. This can be a vital process in helping us deal with depression.

One study by Dr. Greenberg showed that Emotionally Focused Therapy can transform maladaptive emotion through the process of expressing it and eliciting the response of an adaptive emotion, i.e. adaptive anger. This approach was especially effective in improving depressive symptoms, interpersonal distress, and self-esteem. As Dr. Greenberg described it, the process “aims within an affectively attuned empathic relationship to access and transform habitual maladaptive emotional schematic memories [articulated as critical inner voices] that are seen as the source of the depression.” Transforming these maladaptive emotions may, therefore, be one of the keys to fighting depression.

Our approach to transforming anger turned inward, which has some similarities to Greenberg’s approach, is to have the person verbalize their critical inner voices as though someone else was telling them these angry thoughts. We also encourage the person to express the feeling behind the thoughts. Often, when people do this, they express a lot of rage toward self. By saying the thoughts in the second person (as “you” statements), they begin to get some separation from their harsh, critical attitudes, and often have insights about where these thoughts come from. It sets the stage for them “answering back” to these attacks and taking their own side. The goal is also to help the person develop more self-compassion and a kinder, more realistic point of view toward themselves.

As we externalize our negative thoughts and the accompanying anger, we can better stand up to our inner critic and take a compassionate stance toward ourselves, treating ourselves as we would treat a friend. This doesn’t mean denying our struggles and setbacks, but it does mean embracing the practice of self-compassion. Self-compassion, as defined by researcher Kristin Neff, involves three key elements: self-kindness, mindfulness, and awareness of common humanity. Research has shown that the practice of self-compassion can significantly reduce a depressed mood. As one study pointed out, maladaptive or irrational beliefs underlie the development of depression, however, when high levels of self-compassion helped to counteract these negative thoughts, there was no longer a significant relationship between irrational beliefs and depression. This same study showed that it is “especially the self-kindness component of self-compassion that moderated the irrational belief-depression relationship.” Thus, the primary aim for someone struggling with resolving their emotions around depression is to treat themselves and regard their feelings the way they would a friend. It’s not about feeling sorry for ourselves, but about feeling strong and worthy and less afraid to make mistakes.

Ultimately, accepting that anger plays a role in our depression should be an empowering tool in our fight to feel better. When people express anger outwards in a healthy adaptive manner, they feel less depressed. Accessing and expressing this anger isn’t a matter of acting out, being explosive, or feeling bitter toward our surroundings. In fact, it means exactly the opposite. It’s an act of standing up for ourselves and accepting that we are not who our “voices” are telling us we are. It’s a process of facing up to the things that hurt us but also facing off against the inner enemy we all possess that drives us deeper into our suffering. The more we can take our own side and resist our tendency to turn our anger on ourselves, the more compassionate and alive we can feel in facing any challenge, including depression.

Lisa Firestone, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist, author, and the Director of Research and Education for the Glendon Association. She studies suicide and violence as well as couples and family relations. Firestone is the co-author (with Robert Firestone and Joyce Catlett) of Conquer Your Critical Inner Voice, Creating a Life of Meaning and Compassion, and Sex and Love in Intimate Relationships. Firestone speaks frequently at conferences including the APA, the International Association of Forensic Psychology, International Association of Suicide Prevention, the Department of Defense and many others. She has also appeared in more than 300 radio, TV, and print interviews including the BBC, CBC, NPR, the Los Angeles Times, Psychology Today, Men’s Health and O Magazine.