From Nevada Lawyer Magazine, one lawyer argues that young lawyers can reduce stress by taking on one case pro bono that can really change a person’s life. Read the Story

Young Lawyers: Reducing Stress by Taking One More Case

Inspiration for a Grateful Life

In 2001 writer and artist Anne O. Kubitsky printed out 500 invitations asking people to share what they’re grateful for in a postcard and mail it back to her. Read what they wrote

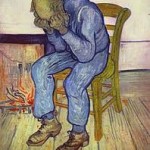

Fighting Back – Changing Belief About Depression

From John Folk-Williams, a piece about how our beliefs about what depression is affects our perspective and healing. Read the Blog

Embracing Mortality, Living Authentically

The subject of mortality may or may not come up overtly in my therapy sessions, but it is always implicit, always hovering about the conversation, always seeking to pull us back down into a special thoughtfulness. Today I was talking with a woman who lamented some of the roads not taken in her life, and, with a chagrined expression, said, “and this is where I will always be, always falling short.”

“What are you so afraid of,” I asked. “It used to be of what people would think, or who would be there to take care of me if I did what I really wanted to do with my life. And today, I guess I am afraid of dying.” “Well, you traded freedom for security and wound up with neither. Isn’t it time you decided it might be worse to relinquish your fearful grip than fear the end of your life?”

If, as is sometimes argued, anything that separates us from nature is pathological, a grand denial, a self-estrangement, or moral evasion, then surely our flight from our mortal nature falls into the “neurotic.” When Jung said “neurosis is the flight from authentic suffering,” he was asserting that we cannot evade suffering, only be captive to its neurotic evasion. Of all of our defenses, our most primitive is denial, greatly abetted by distraction, which is the chief “contribution” our popular culture makes to us. What other culture evolved complex systems to present extravaganzas of sport, exposed flesh, political circus, and programmed violence equal to ours? Well, perhaps ancient Rome, panum et circum, bread and circuses to distract, divert, and entertain the masses. Are we pleased by this comparison?

While it is natural for that slim wafer we call “ego,” namely, who we think we are at any given moment, to bob and wave, and hope the scythe of the Grim Reaper passes over, it is also the surest course to deeper levels of despair and anxiety as inevitability exerts its will. Underneath so many of our neuroses, our pathologies, both private and societal, is the elemental fear of death. This fear is not pathological; it is natural and normal. What becomes pathological is what it makes us do or what it keeps us from doing with our lives.

There are some strange paradoxes to be found here in this fear. Is it not a greater fear to arrive at the end of our journey, however long or short it may prove to be, and recognize that we were not really here, that we did not live our journey? I recall that as a young person I twice walked up to receive an advanced degree thinking, “if I had known they were going to graduate me, I could have enjoyed this whole thing.” I considered then, and even more now, those as rich periods of life lost to anxiety and compulsive coping behavior. I have learned a bit from those and other moments of clarity. At the end of our life would we be inclined to say, “if I knew it was going to end, I could have enjoyed it?”

By “enjoying” I do not mean frivolous wasting of time, or hang-dog obeisance to duty, but having risked investing our energy in whatever provides deep satisfaction to us. If that emotional reciprocity between investment and return is not present, then it is not right for us, however strong our social conditioning. Through our timidity we relinquish the gift of this journey. If there should prove to be an after-life, then it is another life than this one, with another agenda. This is the only one of which we are sure.

Another paradox lies in the fact that it is precisely because our journey is limited that our life has meaning. If we could simply do this or that for a century, and something else for another, then life would lose its bite. The emperor sitting on the veranda with nothing to do but munch grapes and seek diversion has a most miserable life. The slave who lights a fire of freedom in his mind’s eye, the gladiator who says yes to the combat that comes to his door, the woman who sacrifices for her child’s possibilities are infinitely richer. All of them will and do die, but how did they live while here?

So, in the presence of our symptoms: the troubled marriage, the persistent self-sabotage, the eroding addiction, we may all be brought to a larger place by a periodic consideration of mortality. What am I afraid of, really? What shabby excuses are holding me back? What does life ask of me as this point in the journey? Where will I find the most meaningful experiences of my life?

When we ask those questions with sincerity, and summon a measure of courage, we will find that we are too busy living a fuller life to be side-tracked into Angst-ridden swamplands or distracting way-stations. It is all right to be scared; it is not all right to live a scared life.

James Hollis, Ph. D. is a Jungian analyst in Houston, TX, author of 13 books, the most recent of which is What Matters Most: Living a More Considered Life.

Diagnosing Our Depression: Depression in Modern Man

Author and psychiatrist Dr. Nassir Ghaemi looks at the complexity of depression to help unearth some simple frameworks to help people develop the courage to hope. Read the Blog

Meaning is Healthier Than Happiness

The quest for happiness is a dominant theme in contemporary psychology. But according to this article in The Atlantic Magazine, is it healthier than a quest for meaning in one’s life? Read the Blog

Leaving Behind Depression

People with depression tend to hide. They hide their pain. They hide the truth about their suffering because they fear no one will understand. So, they hunker down. They suck it up. They deal with it. Millions of Americans do this every day, seven days a week.

What is the alternative? The polar opposite of hiding seems to be a coming out into the open, a revelation of one’s true self. This involves vulnerability and trust and not a small measure of courage. But it can be done. Millions of Americans do this every day, seven days a week.

I know that in my own life, my hiding began in childhood. Seeking to avoid physical and emotional abuse at the hands of my father, I hid. I did so to be safe. Where would I hide? In the closet behind the hung clothes, the rafters of our garage or the cool and musty basement with the spiders. Sometimes, I would run as fast as I could on summer afternoons into the deep, verdant woods that surrounded my childhood home. I would lay down in the middle of a pine forest with my dog, surrounded by the trees that were my friends, that were my protectors as they hid me from my raging alcoholic father.

Drifting into adulthood, I didn’t let go of my habit of hiding. I had learned that others were not safe or just didn’t care. Like many other depressives, I became a pleaser, an overachiever and a success in my career – all the while hiding a sense of dread that I couldn’t figure out, let alone name.

I now know that I don’t need to hide anymore. I know that it is okay to be my true self with others I care about: my wonderful wife, my precious daughter, friends who are like brothers and sisters to me. Not hiding doesn’t always eliminate depression, but I have come to believe that there is a deep healing that takes place in intimacy that no antidepressant on its best day could match. I have come to believe in the strength and resilience of the human spirit, both mine and others. We won’t always find love and acceptance when we reach out to others. But then again, no one does in this imperfect, fragile and beautiful world. But I do know if we take the risk, if we leave the voices of our childhood that we’re not safe behind, we open ourselves to healing and an end to depression.

Does Finding Purpose in Life Help You Overcome Depression?

Finding purpose in life beyond your personal needs is often a major step in overcoming depression. Read the Blog

Is Therapy Keeping You Stuck, Unhappy Lawyers

From Leaving the Law, read about why lawyers in therapy, and there are lots of them, can get stuck in therapy and not change their lives. Read the Blog

Through A Glass Darkly: An Interview with Miriam Greenspan About Depression

Question: Why do you think it is important for us to pay attention to the dark emotions, in particular?

Greenspan: Actually I think it’s important for us to pay attention to our emotions, in general. Too many people have never learned to do this, because they’ve never been encouraged to do it. We have the notion that our emotions are not worthy of serious attention.

Naturally we have less difficulty with the so-called positive emotions. People don’t mind feeling joy and happiness. The dark emotions are much harder. Fear, grief, and despair are uncomfortable and are seen as signs of personal failure. In our culture, we call them “negative” and think of them as “bad.” I prefer to call these emotions “dark,” because I like the image of a rich, fertile, dark soil from which something unexpected can bloom. Also we keep them “in the dark” and tend not to speak about them. We privatize them and don’t see the ways in which they are connected to the world. But the dark emotions are inevitable. They are part of the universal human experience and are certainly worthy of our attention. They bring us important information about ourselves and the world and can be vehicles of profound transformation.

Question: And if we don’t pay attention to them?

Greenspan: Well, the Buddha taught that we increase our suffering through our attempts to avoid it. If we try to escape from a hard grief, for instance, we may develop a serious anxiety disorder or depression, or we may experience a general numbness. It is difficult to live a full life if we haven’t grieved our losses. I also think that a lot of our addictions have to do with our inability to tolerate grief and despair. Unrecognized despair can turn into acts of aggression, such as homicide or suicide. The same is true of fear. When we don’t have ways to befriend and work with it.

Question: You refer to our culture as “emotion phobic” but suggest that we are also drawn to “emotional pornography.” What do you mean?

Greenspan: By “emotion phobic” I mean that we fear our emotions and devalue them. This fear has its roots in the ancient duality of reason versus emotion. Reason and the mind are associated with masculinity and are considered trustworthy, whereas emotion and the body are associated with the feminine and are seen as untrustworthy, dangerous, and destructive. Nowhere in school, for example, does anyone tell us that paying attention to our emotions might be valuable or necessary. Our emotions are not seen as sources of information. We look at them instead as indicators of inadequacy or failure. We don’t recognize that they have anything to teach us. They are just something to get through or to control.

But despite our fear, there is something in us that wants to feel all these emotional energies, because they are the juice of life. When we suppress and diminish our emotions, we feel deprived. So we watch horror movies or so-called reality shows like Fear Factor. We seek out emotional intensity vicariously, because when we are emotionally numb, we need a great deal of stimulation to feel something, anything. So emotional pornography provides the stimulation, but it’s only ersatz emotion — it doesn’t teach us anything about ourselves or the world.

Question: Other societies seem to have ways of acknowledging the dark emotions. Hindu images come to mind, in which Kali, the goddess of death and rebirth, is sometimes depicted with her mouth dripping blood. Why do you think we are so unwilling to face the dark side of life here in the U.S.?

Greenspan: We have lost our connection to the dark side of the sacred. We prize status, power, consumerism, and distraction, and there is no room for darkness in any of that. Americans tend to have a naiveté about life, always expecting it to be rosy. When something painful happens, we feel that we are no good, that we have failed at achieving a good life. We have no myths to guide us through the painful and perilous journeys of the dark emotions, and yet we all suffer these journeys at some point. We have high rates of depression, anxiety, and addiction in this country, but we have no sense of the sacred possibilities of our so-called illnesses. We have no god or goddess like Kali to guide us. Instead we have a medical culture. Suffering is considered pathology, and the answer to suffering is pharmacology.

Question: So instead of Kali we have Prozac?

Question: So instead of Kali we have Prozac?

Greenspan: Exactly. Our answer to serious pain is a pill that will take it away as quickly as possible. We have no sense that death and rebirth are parts of life. Rather than let suffering expand our consciousness, we succumb to feelings of victimization or treat ourselves as sick. For example, psychiatry has no concept of “normal” despair. We speak only of “clinical depression,” an illness that can be reduced to a neurotransmitter deficiency. Even grief after a major loss is diagnosed as a mental disorder if it lasts more than two months. Our culture tells us to get over our pain; to control, manage, and medicate it. Contrast this with the Jewish practice of “sitting shiva” after a death. For seven days following the burial (shiva means “seven” in Hebrew), the mourners stay at home and sit on low chairs and receive visitors. People come to comfort and console them, to bring food and drink, and to give the mourners a chance to remember their dead and express their grief. Mourning is then gradually stepped down. The seven days are followed by a thirty-day period of mourning, followed by an eleven-month period in which the mourner’s prayer is said twice a day. After that, the dead are remembered once a year.

Instead of making us feel we must “get over it,” these types of rituals allow us to stay open to our grief. Rather than being directed to jump back into our routines, we are given permission to move more organically through the grieving process. After my father died, for example, I sat shiva with my mother, brother, and aunt. When the shiva was over, the rabbi told us to go outside and walk around the block. This was to remind us that the world still turns and life goes on. After the intensity of sitting with our grief for days, there was a sense of renewal, of gratitude for the continuity of life. I was struck by the emotional intelligence of this process. It’s very different from the notion that grief is something we suffer in private, by ourselves, and that it becomes an illness when it goes on for too long.

Question: A recent Forbes article named cognitive-behavioral therapy as the most effective treatment to date for depression and anxiety. By changing our thought patterns, the article suggests, we can eliminate our negative feelings and free ourselves from “long-winded wallowing in past pain.” How would you respond to this?

Greenspan: I think there is great value in becoming more aware of our thoughts and the ways in which they trigger our emotional states. If I am always thinking that I am a horrible person, chances are I will feel depressed. If I think instead, I am a human being, and I am not perfect, and that’s fine, it will inspire more compassion for the self. On the other hand, there are certain experiences that slam us with emotion. People we love die or suffer illness or trauma. We need to learn how to tolerate the emotions that accompany such experiences. We can’t — nor should we try to — simply eliminate these feelings, because this will just entrench them further. Cognitive therapy is great for becoming more aware of our self-destructive thought patterns and how they affect our emotions and behavior, but it doesn’t really address how to befriend intense emotions in the body. If I am awash in grief after my child has died, I need to go through that grief journey; I can’t simply think my way out of it.

Question: Is there an appropriate amount of time for a person to grieve? When do we cross the line into “wallowing”?

Greenspan: It’s always a mistake to designate an “appropriate” time allotment for grief. Everyone has his or her own way of grieving, and the important thing is not to be afraid of grief and to let it unfold, to open up and allow it to bring you on its journey. “Wallowing” is not healthy grief but something else altogether. It’s when we get grandiose about our suffering, get caught up in a victim story, or indulge our emotions without awareness.

Question: What suggestions do you have for people struggling with depression or anxiety?

Greenspan: Well, first of all, they need to accept the fact that they are feeling depressed or anxious. That may sound simple, but it is actually quite hard. It goes against the grain. We are taught that we should not accept these states but rather do whatever we can to put an end to them. But we need to become friendly with the beast, so to speak. We need to be curious: What are these states we call “depression” and “anxiety”? What do they feel like? How do we experience them in the body? This allows us to be moved and transformed by them. It is not the same as “long-winded wallowing in past pain.” I think that depression often eventually lifts of its own accord when we let it be. Most people don’t know this about depression. When we fight depression, it becomes entrenched. There are forms of entrenched depression that are life threatening and do require medication. I am not against medication when necessary; I just believe we too often overuse or abuse psychopharmacological substances for so-called mental disorders, and we don’t search for other ways to deal skillfully with these afflictions.

As for anxiety, we are probably all suffering from heightened anxiety right now if we’re the least bit aware of the problems in the world. I’m not saying that we should allow ourselves to be constantly anxious. We need to know how to soothe ourselves and our loved ones without avoiding the darkness. A simple daily practice of conscious, relaxed breathing is often an antidote for anxiety. Some kind of gratitude practice is also helpful: that is, bringing to mind all that we have to be grateful for every day, and feeling thankful. Even if we don’t feel thankful at the time, it helps to be aware of our blessings.

Question: How would you teach someone to “befriend” his or her suffering?

Greenspan: Emotions live in the body. It is not enough simply to talk about them, to be a talking head. We need to focus our attention on emotions where they live. This willingness to be present allows the emotion to begin to shift of its own accord. An alchemy starts to happen — a process of transmutation from something hard and leaden to something precious and powerful, like gold.

This is a chaotic, nonlinear process, but I think it requires three basic skills: attending to, befriending, and surrendering to emotions in the body. Paying attention to or attending to our emotions is not the same as endless navel gazing and second-guessing ourselves. It is mindfulness of the body, an ability to listen to the body’s emotional language without judgment or suppression.

Befriending follows from focusing our attention and takes it a step further: it involves building our tolerance for distressing emotions. When I was giving birth to my first child, my midwife said something that has stood me in good stead ever since: “When you feel the contraction coming and you want to back away from it, move toward it instead.” The feeling in the body that we want to run away from — that’s precisely what we need to stay with. A simple way to do this is to locate the emotion in the body and breathe through it, without trying to change or end it.

The third skill, surrendering, is the spiritual part of this process. Surrendering to suffering is usually the last thing we want to do, but surrender is what brings the unexpected gifts of wisdom, compassion, and courage. Surrendering is about saying yes when we want to say no — the yes of acceptance. This is what really allows the alchemy to happen. We don’t “let go” of emotions; we let go of ego, and the emotions then let go themselves. This is “emotional flow.” When we let the dark emotions flow, something unexpected and unpredictable often occurs. Consciously experienced, the energy of these emotions flows toward healing and harmony. I’ve found that unimpeded grief transforms itself into heightened gratitude; that consciously experiencing fear expands our ability to feel joy; and that being mindful of despair — really entering into the dark night of the soul with the light of awareness — renews and deepens our faith.

Question: If someone is feeling deep depression or despair, it might feel dangerous to them to “surrender” to what they’re feeling. Is there ever a danger?

Greenspan: “Surrender,” as I’m using it, means a radical acceptance of our emotional experience. We can simply say, “I’m feeling despair right now.” How can that be dangerous? If anything, this acceptance makes it less likely that we will act out of the emotional intensity. The danger comes when we can’t tolerate the discomfort of an emotion and so lose our awareness of it. That’s how emotions overwhelm the mind or impel some kind of impulsive, destructive behavior. It’s not the emotion per se that’s destructive; it’s the behavior that comes from not being able to bear it mindfully.

It sounds odd to us, but what we call “depression” can be a creative process and not just a destructive one. My sense of this probably started to develop when I was a child. My parents are Holocaust survivors, and they were grieving the genocide of their people when I was growing up. Psychiatry would, no doubt, have diagnosed my mother as “depressed.” But, as I see it, she was doing the active grieving she needed to do in order to find a way to live after the enormous trauma of being the sole survivor of her family. She is now ninety-five years old and the most resilient person I know. She’s legally blind and mostly deaf but goes about living her life with an almost Buddha-like acceptance. My father, who died five years ago, came through the Holocaust and still had this amazing and innocent zest for life. I’ve learned a lot from both of them.

Question: You speak of an “alchemy” by which grief can ultimately be transformed into gratitude, fear into joy, and despair into faith. How does that work?

Greenspan: Let’s begin with grief. There is a kind of shattering that happens with, say, the death of a child, or any death, but perhaps most of all violent death. Not only is your heart shattered; you lose your sense of who you are and what your life is about. So reconstruction is needed. But first we need to accept that we are broken. This initiates the “emotional alchemy.” If we can hang in there with grief, it changes from a feeling of being “hemmed in” by life to a feeling of expansion and opening. We will never get back to the way we were, but eventually we reach a new state of “normal.” I’m not talking about the mundane kind of “getting back to normal,” in which we find ourselves doing the laundry again (although that is important too), but the deeper kind, which is a process of remaking ourselves and how we live.

Grief is a teacher. It tells us that we are not alone; that we are interconnected; that what connects us also breaks our hearts — which is as it should be. Most people who allow themselves to grieve fully develop an increased sense of gratitude for their own lives. That’s the alchemy: from grief to gratitude. None of us wants to go through these experiences, but they do bring us these gifts.

The same is true for fear. We think of fear as an emotion that constricts us and keeps us from living fully. But I think it’s really the fear of fear that does this. When we are able to tolerate fear, and to experience it consciously, we learn not to be so afraid of it — and this gives us the freedom to live with courage and enjoy life more fully. This is the alchemy of fear to joy.

We are all living in a heightened fear state now, and being able to tolerate fear is a true gift. Those of us who can live mindfully amid the chaos are doing something for the world as well as for ourselves. It’s essential to be able to bear fear and not go off the edge with it — not allow it to impel us to engage in one form of aggression or another.

Question: It sounds as if you’re saying we need to metabolize the fear somehow.

Greenspan: Yes, that’s a great way to put it. Fear that is not metabolized threatens to destroy us — and perhaps the planet. I’m not saying we need to be in a constant state of anxiety, but we need to know what it is that we are afraid of and not turn our fear into destructive power. My third child, Esther, was born with numerous physical and mental disabilities of unknown origin. She is at risk for all sorts of physical injuries and is in pain a good deal of the time. One day she severely dislocated her knee at summer camp due to her counselors’ neglect, and she came home in a wheelchair. She said, “Summer camp was great — up until the knee-dislocation part!” When I marveled at her cheerfulness and asked what her secret was, Esther said, without missing a beat, “The secret of life is ‘Love people.’ ” She is an amazing soul who lives with fear every day. And every day she has the courage to laugh and love. She teaches me that it’s possible to live fully with pain and fear — which is what courage is all about.

Question: You tell a story in your book about a man whose fear actually informed him of an otherwise invisible and silent danger.

Greenspan: You’re thinking of Adam Trombly, director of the environmental organization Project Earth. Trombly was out walking through a cow pasture on a beautiful day in Rocky Flats, Colorado, when he was suddenly seized by a sense of dread. He regarded his fear as evidence that something was wrong, so he took some soil samples from the area and had them tested. It turned out that the level of plutonium oxide in that spot was thousands of times higher than the acceptable standard. A fire at a nearby nuclear installation had released plutonium oxide into the atmosphere. The accident had not been reported, but Trombly’s fear alerted him to the problem and the coverup. It carried information from the earth. Of course, most scientists would consider this ridiculous or, worse, certifiably psychotic. We don’t honor information brought to us by our feelings, and therefore we don’t learn how to develop our intuitive ways of knowing.

Question: The alchemists had a saying about “finding gold in the dung heap” — literally in the shit. In many ways you are mining the dung heaps of our lives for spiritual and psychological gold.

Greenspan: Yes. “Shit happens,” as they say, and it will continue to happen! I think the hardest thing is to feel that the shit is purposeless. This is at the heart of the emotion we call “despair.” Despair is an existential emotion. It occurs when our meaning system gets shattered and we have to construct a new one. But our culture does not value this process. We don’t see any value in the shit. We want to flush it away. It takes courage to allow our faith and meaning to be dismantled. Despair can be a powerful path to the sacred and to a kind of illumination that doesn’t come when we bypass the darkness. As the poet Theodore Roethke put it, “The darkness has its own light.”

Question: You went through a very difficult time with the death of your firstborn son. Did that experience bring about a process of emotional alchemy in your life?

Greenspan: Aaron was not just an ordeal; he was a blessing. His birth and death were my initiation into the ways of the dark goddess and the occasion of a radical spiritual awakening for me. He was born with a serious brain injury and was destined to live only sixty-six days. There was no apparent reason for this. I was healthy, and I’d had a healthy pregnancy. When he was born, I was an agnostic, a social activist, and a humanist, not a “spiritual” person. My life was centered on the women’s movement. I had no ideas about reincarnation or life after death. I could never have predicted what happened with Aaron.

I remember looking in the mirror on the morning of Aaron’s burial and thinking, I am going to bury my son today. There was an absolute clarity to this. So much of the time our consciousness is not grounded in reality, but at that moment I was able to accept reality. Then, at the cemetery, when we buried Aaron, I heard this clear voice that said, You are looking in the wrong place. I had been looking down at the casket, and when I heard the voice, I raised my eyes. And, looking up, I saw Aaron’s spirit, which I can only describe as a magnificent radiance — like the energy I’d seen in his eyes, only magnified. And the message was that he was ok. I was flooded with a sense of peace. It’s hard to describe because we have no language for these kinds of experiences of spirit. I wouldn’t wish this kind of grief on anyone, yet at the same time, experiencing a baby’s death in your arms and then seeing his spirit leaves you profoundly changed: I became a more grateful person. What I know about emotional alchemy grew from this ground.

Question: I have a friend who recently underwent intensive treatment for cancer that involved a period of isolation — to protect his immune system — and massive chemotherapy. During that time he prayed, meditated, read spiritual writings, and generally stayed “positive.” He felt a great deal of gratitude for his life and for his family and friends, and he kept his mind focused on uplifting things. His approach was an inspiration to me. It was also in keeping with the latest research that suggests negative emotions can make us sick. How does this fit with your idea of healing?

Greenspan: The sacred path of the dark emotions is certainly not the only path there is. It is the path we are on when we are on it, which is usually when we can’t avoid it. But journeys through dark emotions aren’t incompatible with the ability to focus on the light. My daughter Esther went through two spinal-fusion surgeries within one month. If she hadn’t had the surgeries, she would not have lived, but there was no guarantee that she would survive the procedures either. While she was in the hospital, my husband and I tried to be a source of positive energy for her, because it was not the time or place for us to be communicating fear and sorrow. It wasn’t that we didn’t feel scared, but we needed to keep her spirits up. There are times when connecting with “positive” forces, whether through friendships, or reading, or prayer, or simply keeping your sense of humor, is essential. There really is no duality here.

Greenspan: The sacred path of the dark emotions is certainly not the only path there is. It is the path we are on when we are on it, which is usually when we can’t avoid it. But journeys through dark emotions aren’t incompatible with the ability to focus on the light. My daughter Esther went through two spinal-fusion surgeries within one month. If she hadn’t had the surgeries, she would not have lived, but there was no guarantee that she would survive the procedures either. While she was in the hospital, my husband and I tried to be a source of positive energy for her, because it was not the time or place for us to be communicating fear and sorrow. It wasn’t that we didn’t feel scared, but we needed to keep her spirits up. There are times when connecting with “positive” forces, whether through friendships, or reading, or prayer, or simply keeping your sense of humor, is essential. There really is no duality here.

The ability to journey through the dark emotions brings with it the benefit of being more open to the emotions we call “positive,” including joy, pleasure, wonder, awe, and love. When I teach workshops, participants cry, but they also laugh. There is a surprising amount of laughter and humor and just plain fun that comes out of this work.

Question: Do you think negative emotions can make us sick?

Greenspan: Yes, I do, when they are unattended to. When we don’t know how to handle their intense energies, they can become stuck. Research shows that depression and anxiety have a connection to heart disease, immune disorders, cancer, and other ailments. This doesn’t mean that emotions cause cancer. Thinking so makes it easier to ignore research on how environmental contaminants, for instance, are linked to cancer. But stuck emotions do put stress on the body. That’s one reason why mindfulness and the metabolism of emotions are so important. If we don’t digest the emotion, it just sits in our bodies and contributes to ill health.

Question: Is all depression a result of avoiding the dark emotions?

Greenspan: A lot of it is, I think, but certainly not all. Depression is a complex biochemical, psychological, social, and spiritual condition. We call it an “illness” because our culture favors the medical model of explanation. Though it’s perfectly true that depression is correlated with a drop in serotonin levels, this doesn’t mean that serotonin deficiency causes depression. This kind of scientistic reductionism is one of the main drawbacks of our culture’s way of thinking about human problems. Depression is correlated to a lot of things — including gender and a poor economy. It’s also important to make a distinction between despair and depression. Despair is a discrete emotion that, like all emotions, comes and goes; depression is an overall mental and physical state that we might say is chronic, stuck despair.

Question: I think we all want to believe that if we do things “right” — eat the right diet, follow the right spiritual practice, choose the right mode of living — we will be protected somehow from the calamities of life. I have a number of clients in my own therapy practice, for example, who were shocked and hurt to find themselves in the midst of a breakdown even after having done everything right. It was as if life had betrayed them somehow.

Greenspan: I think this is a particularly American mindset, this notion that if we get it all right, we won’t suffer at all. We have even assimilated some Eastern practices through this lens, using them as a strategy for avoiding suffering. We have a hard time tolerating uncertainty. And there is so much uncertainty in this age of terror and environmental crisis. We want to believe there is something we can do that will guarantee a positive outcome and keep us safe. This is an illusion, of course, but sometimes we need our illusions to get us through the day. The illusion I’d had before my son was born was that if I had a healthy pregnancy, exercised, did yoga, and ate well, then everything would turn out fine. I’d even lived with the illusion that because my family history of genocide had involved so much suffering, somehow I would be spared any extreme suffering myself. But my child died, and nobody knew why. I wondered why for a long time. But at some point I realized that “Why?” was the wrong question. There was never going to be an answer. Instead the question was “How?” — how was I going to live now? Illusions are a false way to feel safe. But there is no guaranteed safety. Life is inherently risky, and all we can really do is live well.

Question: For those of us who pursue a spiritual practice, there can be a sense of shame or failure when we feel sad or afraid; if we were enlightened enough, we think, we’d always approach life with a calm, loving heart.

Greenspan: Yes, we carry this mistaken belief that enlightenment means we do not suffer anymore. But it is possible to suffer with a calm, loving heart. These two are not mutually exclusive. Enlightenment for me is about growing in compassion, and compassion means “suffering with.” Enlightenment has something to do with not running from our own pain or the pain of others. When we don’t turn away from pain, we open our hearts and are more able to connect to the best part of ourselves and others — because every human being knows pain. I’m not sure what enlightenment is, but I’m sure it has something to do with turning pain into love.

People with a spiritual practice sometimes try to “transcend” suffering. I call this a “spiritual bypass.” It’s different from what your friend did: focusing on the positive while going through chemotherapy. That was essential to his survival. A spiritual bypass is not a conscious choice; it’s avoiding difficult feelings by “rising above” them, when we are really not above them at all: To truly rise above, most of the time, we must go through. I think there is such a thing as genuine transcendence, but in my experience it is most often a form of grace; we can’t make it happen. A spiritual bypass is a kind of false transcendence. Some New Age ideas carry this flavor: they deny the evils of the world and claim that only love and light are real. This amounts to a dismissal of the pain of millions of people.

Question: Psychologist James Hillman has said, “We cannot be cured apart from the planet.” You point out that our psychological theories — and perhaps some of our spiritual ones as well — emphasize individualism to the point that we have become myopic. Our world is suffering while we struggle to fix ourselves.

Greenspan: One of the main aspects of this myopia is that we don’t see the connection between our “personal” sorrow, fear, and despair and the pain of the world. We think that we are totally alone in it. And the isolation makes our emotions useless to us. There’s a connection between not being able to tolerate our own pain and wanting to look away from other people’s pain and the pain of the world. But the world is always with us. Emotional energy is collective and transpersonal; our seemingly private pain is connected to the larger context that I call “emotional ecology.” I think many of us have a profound emotional sense of global crisis, of the brokenheartedness of the world, and it affects us in ways that we don’t discern.

Of course, we are only human, and sometimes we need to look away, because the pain and chaos are just too much. We numb ourselves — all of us do — to get through the day, to protect ourselves. But psychic numbing is not pleasant — we don’t really feel alive — and it deprives us of our ability to act. Each of us has some gift to give the world. When we become numb, we lose that potential, and the world loses out, too. Staying open-hearted in this era of global threat is really a challenge. Again, my parents have been my models. During the Holocaust, they saw firsthand the worst that humans can do. My father lost eight of his eleven siblings and the rest of his family. But the Holocaust did not destroy his extraordinary openheartedness. He told me once that, after the war, he considered killing some Germans and then killing himself. This was shocking to me; he was such a gentle, loving, and generous man. He had his demons to deal with, but, in the end, he chose to live and raise a family, to put his faith in life. He knew how to maintain a strong connection to the life force even in the midst of a maelstrom of hard emotions.

Question: Even if we’re convinced of the connections between our emotional states and the state of the world, many of us would feel embarrassed to say, “I feel sad today because of the bombings in Iraq,” or, “I’m depressed because of the shrinking ice in Antarctica.”

Greenspan: True, there is no public forum in which we can make statements like this. For that matter, there is very little private space, either. This really is a hindrance — that we do not have an acceptable way to express our sorrow on behalf of the world. We can speak about specific events, like 9/11, but only for a short time, and then the topic is exhausted. There is a taboo about revealing one’s personal emotions about the world — even in a presumably receptive setting. I once took a yoga class in which we were encouraged to state our prayers at the beginning of class. Many people prayed for inner peace. One morning, after having read about the hole in the ozone layer, I prayed for the world. After class, someone angrily said to me, “Why are you bringing the world into the room?” I was baffled and told her that, as I saw it, the world was already in the room, and the room was in the world.

Question: Does the world need us to have feelings about it?

Greenspan: I think so. When I was in retreat at Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health years ago, I had this mystical experience with a beautiful tree. I call myself a “reluctant mystic,” by the way, because I’ve had so many mystical experiences, clairvoyant dreams, and visions that have come to me unbidden. Some of them haven’t been welcome, and none of them can be understood with the analytic mind.

Anyway, at Kripalu, I was walking through this lovely meadow, and I felt a gentle tapping on my shoulder. When I turned around, there was no one there, but I found myself gazing at this spectacular Camperdown-elm tree. I felt as though the tree was calling me, so off I went to it. I touched the tree and had a kind of erotic experience of interspecies communication — of exchanging life forces with it. I felt nourished by the tree and felt that I was giving nourishment in return. After a while I noticed that many of the tree’s leaves had holes in them. I was concerned that the tree might be sick in some way, so I went in search of the groundskeeper, who told me that the elm trees on the property had gotten sick and died. The community had prayed for this tree, because they loved it so much, and it was the sole survivor of the elm disease.

I grew up in the South Bronx and haven’t had extensive experience in nature, but I can tell you that communion with nature is more than just a poetic phrase. One of the most tragic things about our age is that we have lost this communion, and its wonder. With each generation, we lose more of it, and that loss is making us more and more anxious and depressed.

Question: In your book you use the word intervulnerability.

Greenspan: When I say we are “intervulnerable,” I mean we suffer together, whether consciously or unconsciously. Albert Einstein called the idea of a separate self an “optical delusion of consciousness.” Martin Luther King Jr. said that we are all connected in an “inescapable web of mutuality.” There’s no way out, though we try to escape by armoring ourselves against pain and in the process diminishing our lives and our consciousness. But in our intervulnerability is our salvation, because awareness of the mutuality of suffering impels us to search for ways to heal the whole, rather than encase ourselves in a bubble of denial and impossible individualism. At this point in history, it seems that we will either destroy ourselves or find a way to build a sustainable life together.

Question: Just after 9/11, the New Yorker devoted its back page to a poem by Adam Zagajewski titled “Try to Praise the Mutilated World.” I’m sure I am not the only one who had that poem taped to the refrigerator for months after the attacks. In many ways, the path you propose mirrors the poem’s sentiment: we must try to love the mutilated parts of ourselves, just as we must try to love the mutilated parts of our world.

Greenspan: Our mutilated parts and those of the world are interwoven. If we have a child who is crying and needs our attention, we don’t just tell her to “stay positive.” We turn our loving attention to what’s hurting her. We may also try to distract her with an ice-cream cone or a toy, and that’s ok, too. But it’s important that we tend to the parts that are crying. There are so many wounded parts of the world right now, and they keep telling us that they need our loving attention.

Miriam Greenspan holds degrees from Northeastern University, Columbia University, and Brandeis University, and she served on the editorial board of the journal Women and Therapy for a decade. Her first book, A New Approach to Women and Therapy (McGraw-Hill), helped define the field of women’s psychology and feminist therapy in the early eighties. In her most recent book, Healing through the Dark Emotions: The Wisdom of Grief, Fear, and Despair, she argues passionately that the avoidance of the dark emotions is behind the escalating levels of depression, addiction, anxiety, and irrational violence in the U.S. and throughout the world.

Her therapeutic approach encourages what she calls “emotional alchemy,” a process by which fear can be transformed into joy, grief into gratitude, and despair into a resilient faith in life. She questions the prevailing psychiatric attitude toward grief and despair, which relies heavily upon psychopharmacology to return us as quickly as possible to a “normal” state. Her focus is on transformation rather than normalcy.

This interview first appeared in the January 2008 edition of The Sun Magazine. All rights are reserved by The Sun.

Built by Staple Creative