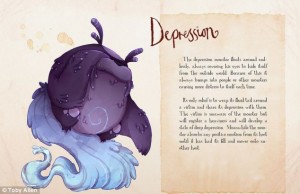

Depression will push our backs up against the wall. It often seems bigger than us: a bully. If we let it, it will pound us down. So, we’ve got to push back.

If we don’t fight back, together with the help of others, depression can consume our lives leaving only our pulse and some air in our lungs, but precious little else. The vitality, the passion and full array of emotions that make life worth living may be sucked up out of us as if by an alien ship from above.

There are many tools to fight depression. They can certainly help us regain our footing and make our lives functional and productive again. But isn’t life more than just about a return to “normal”? We all have dreams and aspire to live them. Theres’s something wild about dreams. So often, they are outside our “normal”. And regaining them is a big part of recovery for it is these passions that bring us most fully alive in the cosmos. And we have to fight for our dreams.

Just like fighting a bully, pushing back against depression takes courage. We have to reach deep down inside ourselves to listen to that part of our life force in us all that gives us the grit to say to depression,“no more”. We must say to ourselves, “I’m sick and tired of being ‘sick and tired’”.

When we’re ready to make some changes, we push the bully back. A small push in the beginning will do. We gain some space and separation from this goblin. We stop defining ourselves as a “depressed person,” as if our identity were wholly made up of our affliction. We are not our depression. It is a part, albeit a very painful part, of our lives. But it need not be all of it.

To fight back against depression, we need to empower ourselves to level the playing field. One of the best ways is learn mindfulness. With it, we gain detachment from our negative thoughts and emotions. Mindfulness teaches us that pessimistic thoughts and disturbing emotions are clouds passing in the sky, not reality. Check out the excellent book, The Mindful Way Through Depression to learn more.

If we don’t buy into the depressed stories our minds spin out, we can begin to see them for what they are: puffs of cerebral and neurochemical smoke. We don’t have to buy into them. We don’t have to live by that script.

This takes a lot of practice and we have to start slowing. This is, by no means, a quick “fix”. But in detaching ourselves from our mental jumble and the over reactive emotions that accompany my anxiety and depression, we gain freedom. We again have choices in life. We need not walk in the deep ruts of depression anymore.

And this is empowering.

Poet, Mary Oliver in her poem, “The Journey,”beautifully captures the sense of determination we need to recover from depression:

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice–

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voices behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do–

determined to save

the only life you could save.