As a psychiatrist, I had been aware, prior to his death, that Robin Williams struggled with a severe mood disorder – major depression and bipolar disorder, depending on the source of the reporting – along with related problems and drug dependence.

The vast majority of suicides are associated with some form of clinical depression, which in its more serious forms can be a sort of madness that drives people to despair – leading to a profound and painful sense of hopelessness and even delusional thinking about oneself, the world and the future.

I knew all of this, and yet this death still shocked and surprised me, as it shocked and surprised so many others. Williams seemed to be the consummate humorist, the funny man who would be just so much fun to be around. Unlike some comedians who trade only on irony and cutting humor, Williams appeared to us as a warm, big-hearted, endlessly fun, brilliantly quick, incredibly talented man. Though he was a celebrity, he was the kind of person that people felt like they knew – like the cousin, everyone just adores and hopes will show up at the family reunion. Williams was the kind of guy that people wanted to be friends with, the kind of person that one wanted to invite to the party.

This is not the typical stereotype of mental illness, which why the typical stereotype must be relinquished: Quite simply, it is false.

Mental illness can afflict anyone, of any temperament and personality. In the wake of his death, the strange truth gradually began to sink in: In spite of outward appearances, Williams’ mind was afflicted by a devastating disorder that proved every bit as deadly as a heart attack or cancer. He suffered in ways that are difficult for most people to imagine.

Why couldn’t Williams see himself as other saw him – as a person of immense gifts and talents, a man who stood at the pinnacle of achievement in the world of comedy and entertainment?

Why couldn’t he see himself as God saw him – as a beloved child, a human soul of immense worth, a person for whom Christ died?

This is the tragedy of depression, which is so often misunderstood by those who have not suffered its effects.

Novelist William Styron – whose memoir Darkness Visible represents one of the best first-person attempts to describe the experience of depression – complains that the very word “depression” is a pale and inadequate term for such a terrible affliction. It is a pedestrian noun that typically represents a dip in the road or an economic downtown. Styron prefers the older term “melancholia,” which conjures images of a thick, black fog that descends on the mind and saps the body of all vitality.

Indeed, the title of his book – Darkness Visible – comes from John Milton’s description of hell in Paradise Lost. We’re not talking about hitting a rough patch in life or the everyday blues that we all experience from time to time. We are talking about a serious, potentially fatal, disorder of mind and brain.

Fortunately, in most cases, depression is amenable to treatment. Because the illness is complex – involving biological, psychological, social, relational and, in some cases, behavioral and spiritual factors – the treatment likewise can be complex. Medications may have a very important role, but so do psychotherapy, behavioral approaches, social support and spiritual direction.

In some cases, hospitalization may be necessary, especially when an afflicted individual is in the throes of suicidal thinking or when one’s functioning is so impaired from the illness that he or she has difficulty getting out of bed or engaging in daily activities. For the severely depressed, even brushing one’s teeth can seem like an almost impossibly difficult chore.

This level of impairment is often puzzling to outsiders – to the spouse or parent who is trying to help the loved one. Unlike cancer or a broken bone, the illness here is hidden from sight. But the functional impairments can be every bit as severe.

I recall one patient, a married Catholic woman with several children and grandchildren, who had suffered from both life-threatening breast cancer and from severe depression. She once told me that, if given the choice, she would choose cancer over the depression, since the depression caused her far more intense suffering. Though she had been cured of cancer, she tragically died by suicide a few years after she stopped seeing me for treatment.

Depression is neither laziness nor weakness of will, nor a manifestation of a character defect. It needs to be distinguished from spiritual states, such as what St. Ignatius described as spiritual desolation and what St. John of the Cross called the dark night of the soul.

Tragically, even with good efforts aimed at treatment, some cases of depression still lead to suicide – leaving devastated family members who struggle with loss, guilt, and confusion.

The Church teaches that suicide is a sin against love of God, love of oneself and love of neighbor. On the other hand, the Church recognizes that an individual’s moral culpability for the act of suicide can be diminished by mental illness, as described in the Catechism: “Grave psychological disturbances, anguish or grave fear of hardship, suffering or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide.”

The Catechism goes on to say: “We should not despair of the eternal salvation of persons who have taken their lives. By ways known to him alone, God can provide the opportunity for salutary repentance. The Church prays for persons who have taken their own lives.”

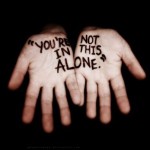

Robin Williams’ death – like the death of so many others by suicide who have suffered from severe mental illness – issued from an unsound mind afflicted by a devastating disorder. Depression affects not just a person’s moods and emotions; it also constricts a person’s thinking – often to the point where the person feels entirely trapped and cannot see any way out of his mental suffering. Depression can destroy a person’s capacity to reason clearly; it can severely impair his sound judgment, such that a person suffering in this way is liable to do things, which, when not depressed, he would never consider. Our Lord’s ministry was a ministry of healing, in imitation of Christ, we are called to be healers as well. Those who suffer from mental-health problems should not bear this cross alone. As Christians, we need to encounter them, to understand them and to bear their burdens with them.

Robin Williams’ death – like the death of so many others by suicide who have suffered from severe mental illness – issued from an unsound mind afflicted by a devastating disorder. Depression affects not just a person’s moods and emotions; it also constricts a person’s thinking – often to the point where the person feels entirely trapped and cannot see any way out of his mental suffering. Depression can destroy a person’s capacity to reason clearly; it can severely impair his sound judgment, such that a person suffering in this way is liable to do things, which, when not depressed, he would never consider. Our Lord’s ministry was a ministry of healing, in imitation of Christ, we are called to be healers as well. Those who suffer from mental-health problems should not bear this cross alone. As Christians, we need to encounter them, to understand them and to bear their burdens with them.

We should begin with the premise that science and religion, reason and faith are in harmony. Our task is to integrate insights from all these sources – medicine, psychology, the Bible, and theology – in order to understand mental illness and to help others to recover from it. In cases where recovery proves difficult or impossible, we pray for the departed and never abandon those who still struggle.

Aaron Kheriaty, M.D., is associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the University of California-Irvine School of Medicine. He is the co-author with Msgr. John Cihak of The Catholic Guide to Depression.