Lawyers face challenges unlike those found in many other professions. The combination of long hours, time away from family, pressure to find (and keep) clients, stress, and the ever-present focus on the bottom line does not leave much room for balance or a general sense of well-being. This article analyzes why the journey into the legal profession can be difficult and provides research-based solutions to move toward a culture of positive professionalism. The goal is not to present a jaded, self-help view of how to fix the unhappy masses, but rather, to present an empirical, research-based framework to initiate a new conversation within the legal profession. Read the blog.

The Science of Well-Being and the Legal Profession

New Research Shows Depression Linked With Inflammation

Dr. Marylynn Wei writes, “One traditional hypothesis of depression is that people who are depressed have a deficiency in monoamine neurotransmitters in the body, which leads to low levels of neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain. But growing evidence supports that at least some forms of depression may also be linked to ongoing low-grade inflammation in the body. Brain imaging of people with depression show that their brain scans have increased neuroinflammation. When your body is in an inflammatory state fighting off the common cold or flu, you can experience symptoms overlapping with depression— disrupted sleep, depressed mood, fatigue, foggy-headedness, and impaired concentration.” Read the rest of her blog.

Even Lawyers Need Play

Lawyer Ruth Carter blogs at Attorneyatwork.com: “Captain Kirk, in a TV episode of “Star Trek,” says, “The more complex the mind, the greater the need for the simplicity of play.” Playing is not something I do easily or often. Even in my youth, it was easier to get me to eat brussels sprouts than do something purely for fun. However, I’ve come to accept that playing is a necessity for sanity, to offset the high-stress lawyer lifestyle. Sometimes I wonder how other people have so much room for downtime when my nights and weekends are filled with errands, chores, working out and writing blog posts. Where does everyone find time for frivolity?” Read the entire blog.

Rediscovering Who You Are After a Severe Depressive Episode

Blogger Joy Biddell writes, “But what I’m finding even harder than mundane tasks is rediscovering who I am. Depression stole my identity and my joy. Trying to find myself again while still feeling exhausted, low and riddled with anxiety is one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. Everything I knew and enjoyed feels like a distant memory and building myself back up feels like an impossible task. I can’t remember what genuine happiness feels like. I’ve had glimpses of it, but the feeling doesn’t stick around. I can’t remember how to socialize, even texting friends is difficult. I used to enjoy coloring, church, volunteering, reading, driving with tunes blasting and singing at the top of my voice (even in traffic), going out with friends, going for meals out, long walks with the dogs, my partner and seeing family. All these things are incredibly hard to do now. I either can’t remember how to do them, get too anxious and overwhelmed to do them or physically can’t do them.” Read her full blog here.

Diving Into Hell: A Powerful Memoir of Depression

From The New York Times, book reviewer and best-selling author Andrew Solomon writes, “Not so long ago, the mere fact of writing that you had suffered from depression conferred a badge of courage, but such confessions have devolved into a dull mark of solipsistic forthrightness. Famous people use such disclosures to persuade you that they are just like you, perhaps even more vulnerable; it’s a way of compensating for the discomfort attached to their glamor. Indeed, in an increasingly stratified world, people with any modicum of privilege may reveal their depression as an assertion of their common humanity. Clinical misery has taken over from death as the great equalizer. Vanity of vanities, all is depression. Into this morass daringly comes Daphne Merkin with the long-awaited chronicle of her own consuming despair, ‘This Close to Happiness: A Reckoning with Depression.'” Read the entire article here.

3 Practices for Letting Go of Looping Thoughts

Jenna Cho, lawyer and author of the book, “The Anxious Lawyer” writes, “The ability to gently let go of negative looping thoughts has been perhaps one of the most powerful and unexpected benefits of having a regular meditation practice. Research indicates that meditation can help us process and decrease the impact of negative emotions, such as anger. If you find yourself stuck in an endless negative thought loop, here are three practices that you may find useful.” Read the entire blog here.

Changing Is Hard

A Canadian blogger by the name of Michelle (no last name given) writes, “Changing is hard. Okay, lots of things are hard when you’re depressed. Getting up in the morning. Finding the energy to do everyday tasks. Looking for the will to go on. You know, all that good stuff. But changing yourself and your thoughts is especially hard.It’s a strange battle, isn’t it? Often, you know what you ought to do or have to do. And often, you just can’t seem to summon up the will to do it.” Read her entire blog here.

Coming to Terms With Depression

In her new memoir, This Close to Happy, Daphne Merkin writes about how she’s made her way through life, not despite, but with depression. She tells NPR’s Scott Simon that sometimes she just has to push herself through bad days. “At really bad times, I will admit I don’t get up,” she says. “I sort of languish, or sleep. But mostly I try and combat it by assertions of will. Which is not the same as saying, ‘Pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’ though … there’s a point at which these assertions of will don’t help. But otherwise, I think there’s a way of negotiating depression, like, talking to it. Saying, ‘you can do this, you’ll be OK, try going outside, try sitting at your desk.’ You know, kind of coaxing oneself.” Listen to the interview here.

On Depression, Hope, Hopelessness, and Freedom

Hope is a desire for something combined with an anticipation of it happening, it is the anticipation of something desired. To hope for something is to make a claim about something’s significance to us, and so to make a claim about ourselves.

One opposite of hope is fear, which is the desire for something not to happen combined with an anticipation of it happening. Inherent in every hope is a fear, and in every fear a hope. Other opposites of hope are hopelessness and despair, which is an agitated form of hopelessness.

Hope is often symbolized by harbingers of spring such as the swallow, and there is a saying that ‘there is no life without hope’. Hope is an expression of confidence in life, and the basis for more practical dispositions such as patience, determination, and courage. It provides us not only with aims but also with the motivation to attain those aims. As the theologian, Martin Luther said, ‘Everything that is done in the world is done by hope.’ Hope not only looks to the future but also makes present hardship easier to bear, sustaining us through our winters.

At a deeper level, hope links our present to our past and future, providing us with an overarching narrative that lends shape and meaning to our life. Our hopes are the strands that run through our life, defining our struggles, our successes and setbacks, our strengths and shortcomings, and in some sense ennobling them. Running with this idea, our hopes, though profoundly human—because only humans can project themselves into the distant future—also connect us with something much greater than ourselves, a cosmic life force that moves in us as it does in all of nature. Conversely, hopelessness is both a cause and a symptom of depression, and, in the context of depression, a strong predictor of suicide. “What do you hope for out of life?” is one of my most important questions as a psychiatrist, and if my patient replies “nothing” I have to take that very seriously.

Hope is pleasant in so far as the anticipation of a desire is pleasant. But hope is also painful, because the desired circumstance is not yet at hand, and, moreover, may never be at hand. Whereas realistic or reasonable hopes are more likely to lift us up and move us on, false hopes are more likely to prolong our torment, leading to inevitable frustration, disappointment, and resentment. The pain of harboring hopes, and the greater pain of having them dashed explains why most people tend to be modest in their hoping.

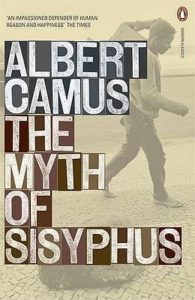

In his essay of 1942, The Myth of Sisyphus, the philosopher Albert Camus compares the human condition to the plight of Sisyphus, a mythological king of Ephyra who was punished for his chronic deceitfulness by being made to repeat forever the same meaningless task of pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll back down again. Camus concludes, ‘The struggle to the top is itself enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’

Even in a state of utter hopelessness, Sisyphus can still be happy. Indeed, he is happy precisely because he is in a state of utter hopelessness, because in recognizing and accepting the hopelessness of his condition, he at the same time transcends it.

Neel Burton, M.D., is a psychiatrist, philosopher, writer, and wine lover who lives and teaches in Oxford, England. He is a Fellow of Green-Templeton College, Oxford, and the recipient of the Society of Authors’ Richard Asher Prize, the British Medical Association’s Young Authors’ Award, the Medical Journalists’ Association Open Book Award, and a Best in the World Gourmand Award.He is author of Heaven and Hell: The Psychology of the Emotions, Hide and Seek: The Psychology of Self-Deception, and other books.

The Bald-Faced Lies Depression Tells Us

Whatever the cause, clinical depression sufferers are often shackled to a prison of ruminative, negative thoughts about the world and themselves.

They are full of self-loathing, feelings of worthlessness, and a sense of failure. Confidence in their ability to build and maintain successful relationships is eroded. Their sense of competency about their work can plummet as they struggle to get things done, be productive and earn a living. Some may even hate themselves when lost in this destructive process.

If that weren’t tough enough, are brains actually work against in this negative spiral. Psychologist Margaret Wehrenberg writes:

“Brain function plays a role in rumination in several ways, but one significant aspect

Built by Staple Creative